Strict Mode

StrictMode is a tool for highlighting potential problems in an application. Like Fragment, StrictMode does not render any visible UI. It activates additional checks and warnings for its descendants.

Note:

Strict mode checks are run in development mode only; they do not impact the production build.

You can enable strict mode for any part of your application. For example:

import React from 'react';

function ExampleApplication() {

return (

<div>

<Header />

<React.StrictMode> <div>

<ComponentOne />

<ComponentTwo />

</div>

</React.StrictMode> <Footer />

</div>

);

}In the above example, strict mode checks will not be run against the Header and Footer components. However, ComponentOne and ComponentTwo, as well as all of their descendants, will have the checks.

StrictMode currently helps with:

- Identifying components with unsafe lifecycles

- Warning about legacy string ref API usage

- Warning about deprecated findDOMNode usage

- Detecting unexpected side effects

- Detecting legacy context API

- Detecting unsafe effects

Additional functionality will be added with future releases of React.

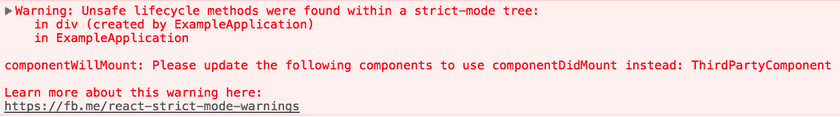

Identifying unsafe lifecycles

As explained in this blog post, certain legacy lifecycle methods are unsafe for use in async React applications. However, if your application uses third party libraries, it can be difficult to ensure that these lifecycles aren’t being used. Fortunately, strict mode can help with this!

When strict mode is enabled, React compiles a list of all class components using the unsafe lifecycles, and logs a warning message with information about these components, like so:

Addressing the issues identified by strict mode now will make it easier for you to take advantage of concurrent rendering in future releases of React.

Warning about legacy string ref API usage

Previously, React provided two ways for managing refs: the legacy string ref API and the callback API. Although the string ref API was the more convenient of the two, it had several downsides and so our official recommendation was to use the callback form instead.

React 16.3 added a third option that offers the convenience of a string ref without any of the downsides:

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.inputRef = React.createRef(); }

render() {

return <input type="text" ref={this.inputRef} />; }

componentDidMount() {

this.inputRef.current.focus(); }

}Since object refs were largely added as a replacement for string refs, strict mode now warns about usage of string refs.

Note:

Callback refs will continue to be supported in addition to the new

createRefAPI.You don’t need to replace callback refs in your components. They are slightly more flexible, so they will remain as an advanced feature.

Learn more about the new createRef API here.

Warning about deprecated findDOMNode usage

React used to support findDOMNode to search the tree for a DOM node given a class instance. Normally you don’t need this because you can attach a ref directly to a DOM node.

findDOMNode can also be used on class components but this was breaking abstraction levels by allowing a parent to demand that certain children were rendered. It creates a refactoring hazard where you can’t change the implementation details of a component because a parent might be reaching into its DOM node. findDOMNode only returns the first child, but with the use of Fragments, it is possible for a component to render multiple DOM nodes. findDOMNode is a one time read API. It only gave you an answer when you asked for it. If a child component renders a different node, there is no way to handle this change. Therefore findDOMNode only worked if components always return a single DOM node that never changes.

You can instead make this explicit by passing a ref to your custom component and pass that along to the DOM using ref forwarding.

You can also add a wrapper DOM node in your component and attach a ref directly to it.

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

this.wrapper = React.createRef(); }

render() {

return <div ref={this.wrapper}>{this.props.children}</div>; }

}Note:

In CSS, the

display: contentsattribute can be used if you don’t want the node to be part of the layout.

Detecting unexpected side effects

Conceptually, React does work in two phases:

- The render phase determines what changes need to be made to e.g. the DOM. During this phase, React calls

renderand then compares the result to the previous render. - The commit phase is when React applies any changes. (In the case of React DOM, this is when React inserts, updates, and removes DOM nodes.) React also calls lifecycles like

componentDidMountandcomponentDidUpdateduring this phase.

The commit phase is usually very fast, but rendering can be slow. For this reason, the upcoming concurrent mode (which is not enabled by default yet) breaks the rendering work into pieces, pausing and resuming the work to avoid blocking the browser. This means that React may invoke render phase lifecycles more than once before committing, or it may invoke them without committing at all (because of an error or a higher priority interruption).

Render phase lifecycles include the following class component methods:

constructorcomponentWillMount(orUNSAFE_componentWillMount)componentWillReceiveProps(orUNSAFE_componentWillReceiveProps)componentWillUpdate(orUNSAFE_componentWillUpdate)getDerivedStateFromPropsshouldComponentUpdaterendersetStateupdater functions (the first argument)

Because the above methods might be called more than once, it’s important that they do not contain side-effects. Ignoring this rule can lead to a variety of problems, including memory leaks and invalid application state. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to detect these problems as they can often be non-deterministic.

Strict mode can’t automatically detect side effects for you, but it can help you spot them by making them a little more deterministic. This is done by intentionally double-invoking the following functions:

- Class component

constructor,render, andshouldComponentUpdatemethods - Class component static

getDerivedStateFromPropsmethod - Function component bodies

- State updater functions (the first argument to

setState) - Functions passed to

useState,useMemo, oruseReducer

Note:

This only applies to development mode. Lifecycles will not be double-invoked in production mode.

For example, consider the following code:

class TopLevelRoute extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

SharedApplicationState.recordEvent('ExampleComponent');

}

}At first glance, this code might not seem problematic. But if SharedApplicationState.recordEvent is not idempotent, then instantiating this component multiple times could lead to invalid application state. This sort of subtle bug might not manifest during development, or it might do so inconsistently and so be overlooked.

By intentionally double-invoking methods like the component constructor, strict mode makes patterns like this easier to spot.

Note:

Starting with React 17, React automatically modifies the console methods like

console.log()to silence the logs in the second call to lifecycle functions. However, it may cause undesired behavior in certain cases where a workaround can be used.

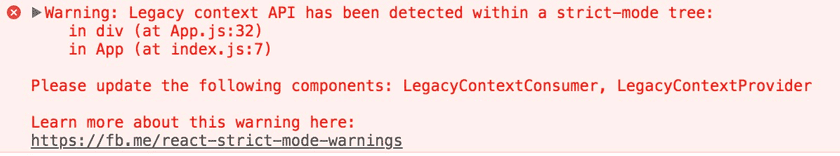

Detecting legacy context API

The legacy context API is error-prone, and will be removed in a future major version. It still works for all 16.x releases but will show this warning message in strict mode:

Read the new context API documentation to help migrate to the new version.

Detecting unsafe effects

Conceptually, React effects include three phases:

- The create phase is called for all effects when the effect is created.

- The update phase is called when the dependencies change, if applicable.

- The destroy phase is called for all effects when the effect is destroyed.

In the past, React has only called the create phase once when a component mounts:

* React mounts the component.

* Layout effects are created.

* Effect effects are created.and the destroy phase once when a component unmounts:

* React unmounts the component.

* Layout effects are destroyed.

* Effect effects are destroyed.Note:

It’s common to hear effects being “mounted” and “unmounted”. This is because effects have historically been created when a component was mounted, and destroyed when a component was unmounted. This can cause confusion, so we refer to them as “created” and “destroyed” here instead.

In the future, we’d like to add features to React which would allow a component to mount without immediately creating effects (such as pre-rendering), or to destroy effects in already-mounted components (such as when a component isn’t visible). These features will add better performance and resource management out-of-the-box to React, but require effects to be decoupled from the component lifecycle and resilient to being created and destroyed multiple times in a component.

To help surface these issues, React 18 introduced Strict Effects to Strict Mode.

With Strict Effects, React will automatically destroy and re-create every effect in development, whenever a component mounts:

* React mounts the component.

* Layout effects are created.

* Effect effects are created.

* React simulates effects being destroyed on a mounted component.

* Layout effects are destroyed.

* Effects are destroyed.

* React simulates effects being re-created on a mounted component.

* Layout effect setup code runs

* Effect setup code runswhen the component unmounts, effects are destroyed as normal:

* React unmounts the component.

* Layout effects are destroyed.

* Effect effects are destroyed.Note:

This only applies to development mode. Strict Effects will not run in production mode.

For more information, see: